Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) are more affordable than their combustion engine counterparts (ICEVs) and no longer require the support of the purchase subsidy, our total cost of ownership analysis shows. This is primarily the case for situations where home charging is available. Being dependent on public or fast charging may flip the coin. studio Gear Up argues that more should be done to accelerate the uptake of electric vehicles for lower income groups. Our analysis concludes that the selected EVs are already on par or cheaper in use compared to the equivalent vehicles with a combustion engine. Still, these models are, on basis of the catalogue price only within reach for the highest income quintile of households in the Netherlands.

The Netherlands passenger car sales market is dominated by sales of used cars. In 2023 Dutch car dealers and companies sold 1.39 million versus 0,37 million new vehicles.[1 – footnotes at bottom of the blog] Also at European level this trend is visible.[2] The further uptake of electric vehicles could be accelerated by redirecting the budgets and lowering the ceiling of the existing Private Electric Passenger Car Subsidy[3] towards the purchase of used electric vehicles, and in particular be targeted to households in the lower income quintiles.

BEVs: Higher priced, but lower in cost

Even though battery-electric cars’ (BEV) catalogue prices are still higher than those of their internal combustion engine vehicle (ICEV) equivalents, the price gap has narrowed down in the last few years in the Netherlands. To gain better understanding of the affordability of BEVs compared to ICEVs within the Netherlands, we have analysed six popular passenger cars – three battery electric vehicles and their three combustion engine equivalents – on the basis of their total cost of ownership (TCO).

The results are showing that BEVs have lower costs based on a 5-year ownership period compared to their ICEV counterparts – even without an initial purchase subsidy. However, where the car is charged has a significant effect on the total cost of ownership as charging prices highly differ. The comparison of four charging modes – home charging with an energy contract, home charging with solar panel, public charging and public fast charging – unveiled that home charging with solar panels is the most cost-effective option.

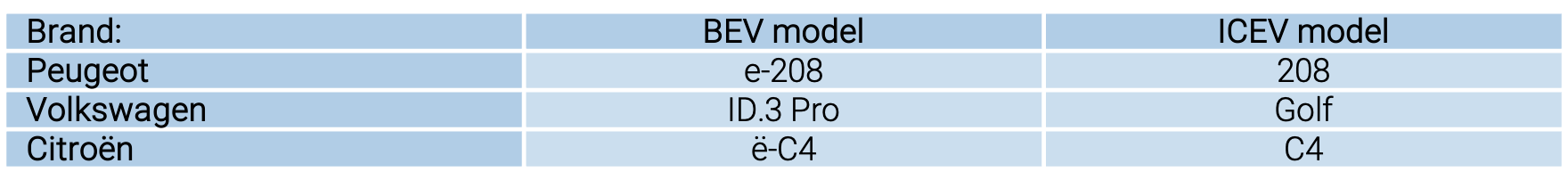

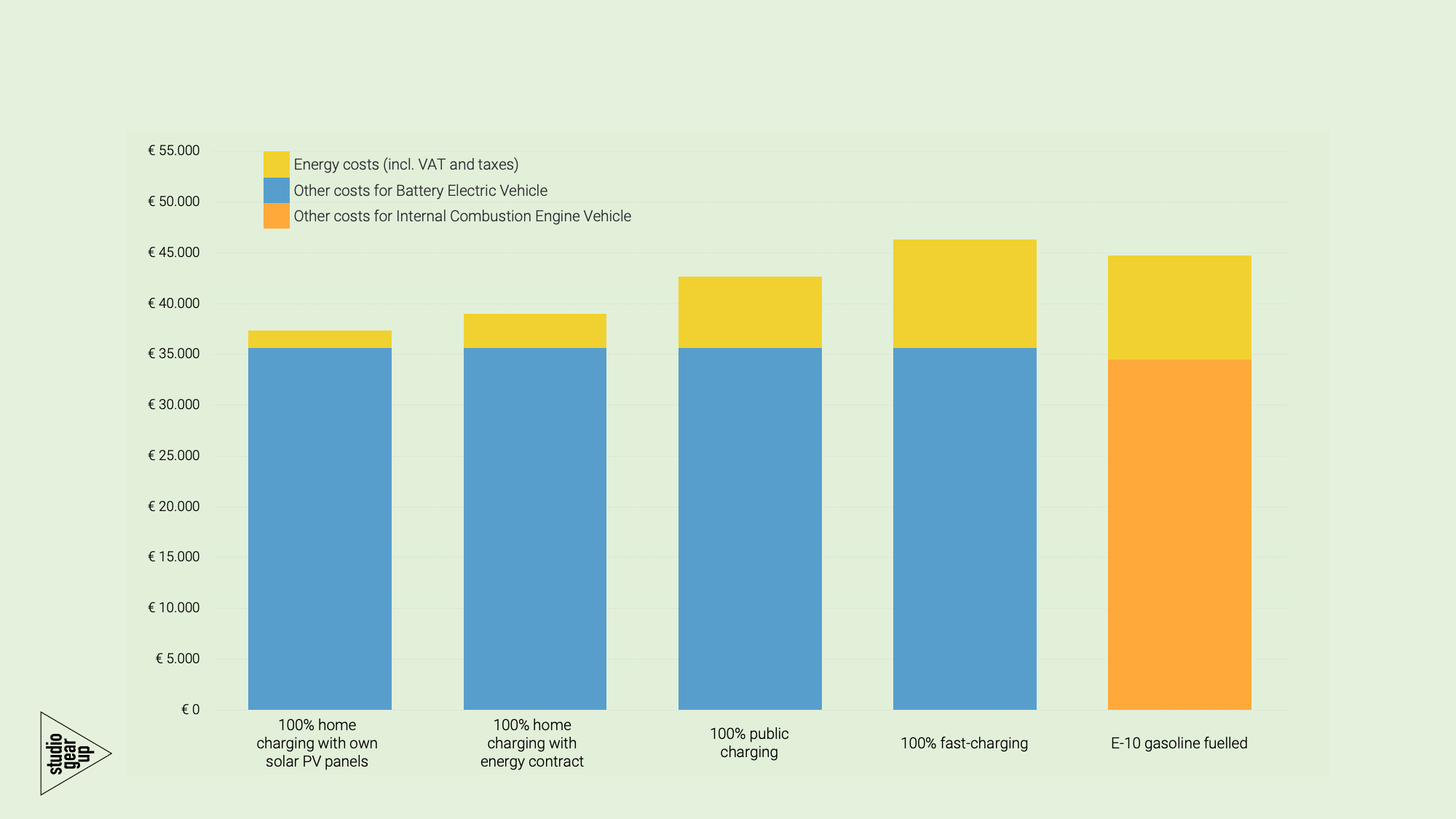

The total cost of ownership is one of the most important indicators to judge affordability of vehicles. By comparing the total cost of ownership (TCO) of BEVs to the TCO of ICEVs a comprehensive understanding of the different cost elements and the interactions of those could be gained. We looked at six popular passenger car models in the Dutch market:

The cars were selected based on their popularity (ICEVs) – not only in the Netherlands, but in seven other EU Member States as well – and whether they have a BEV equivalent.

Purchase subsidy for BEVs will need to be redirected

The purchase of the battery electric vehicles (BEVs) is subsidised by the Dutch government in order to support the achievement of its climate goals, particularly the ambition of 100% of new cars sold to be emission-free by 2030. The subsidy scheme largely entails tax exemption from registration tax (BPM) and road tax (until 2025) combined with a purchase subsidy (in 2024) equal to € 2,950 for newly bought passenger cars. The total budget of the purchase subsidy is € 58 million for 2024 for new vehicles, under the condition that the catalogue price is less than € 45,000. A purchase subsidy is also available for used BEVs in the form of a € 2,000 support from the government. The total budget for purchasing used BEVs is € 29.4 million for 2024 and only eligible for selected models with an original catalogue price up to € 45,000.

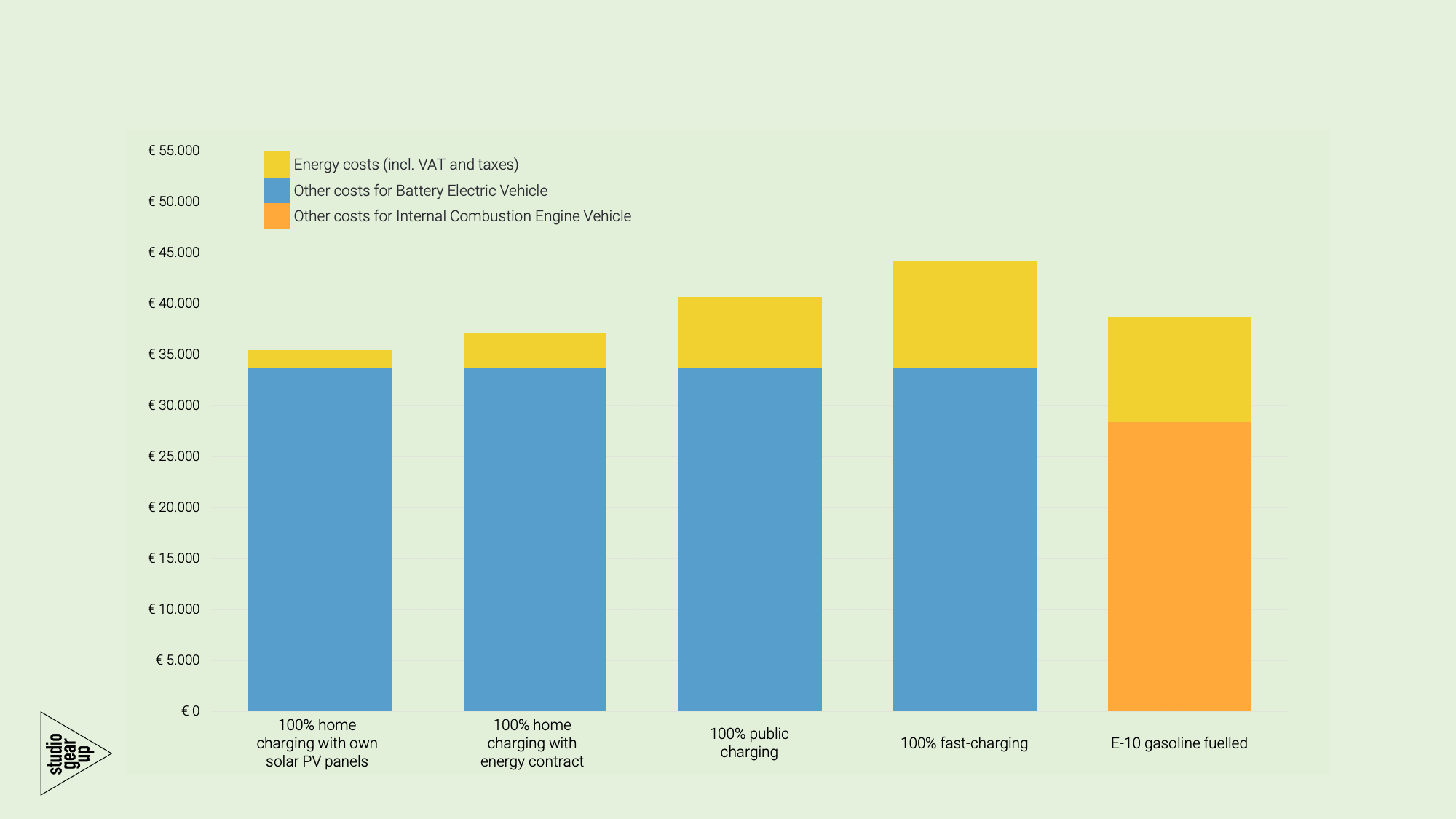

If the Dutch government were to discontinue the purchase subsidy for new BEVs (€ 2,950) then all BEVs considered in our analysis are still viable, de facto, cheaper choices for consumers on the basis of a 5-year TCO when they are enabled to charge their BEVs at home with energy contract. Figure 1 shows how the total cost of ownership of BEVs with and without purchase subsidy are compared to their ICEV counterparts for a 5-year ownership period driven 20 thousand km/year, on basis of home charging with an energy contract.

Even without a purchase subsidy, both the Volkswagen ID.3 and Citroen ë-C4 are considerably cheaper options compared to their ICEV counterparts, while the Peugeot e-208 has somewhat lower costs during a 5-year ownership period when only regular home charging is assumed. This analysis should be extended to include models of other OEMS, but these selected BEVs are competitive and less costly choices in comparison to their ICEV equivalents regardless the presence of a purchase subsidy. However, if the road tax (Motorrijtuigenbelasting), which is set to be applicable to BEVs first with 25% in 2025 then 100% from 2026, will be based on the higher weight this will impact negatively the TCO of the BEVs compared to ICEVs.

For a detailed cost breakdown of the TCO of BEVs with home charging with energy contract and ICEVs, see Figure 8 and Figure 9 in the Annex.

The mode of charging determines the cost-effectiveness of BEVs

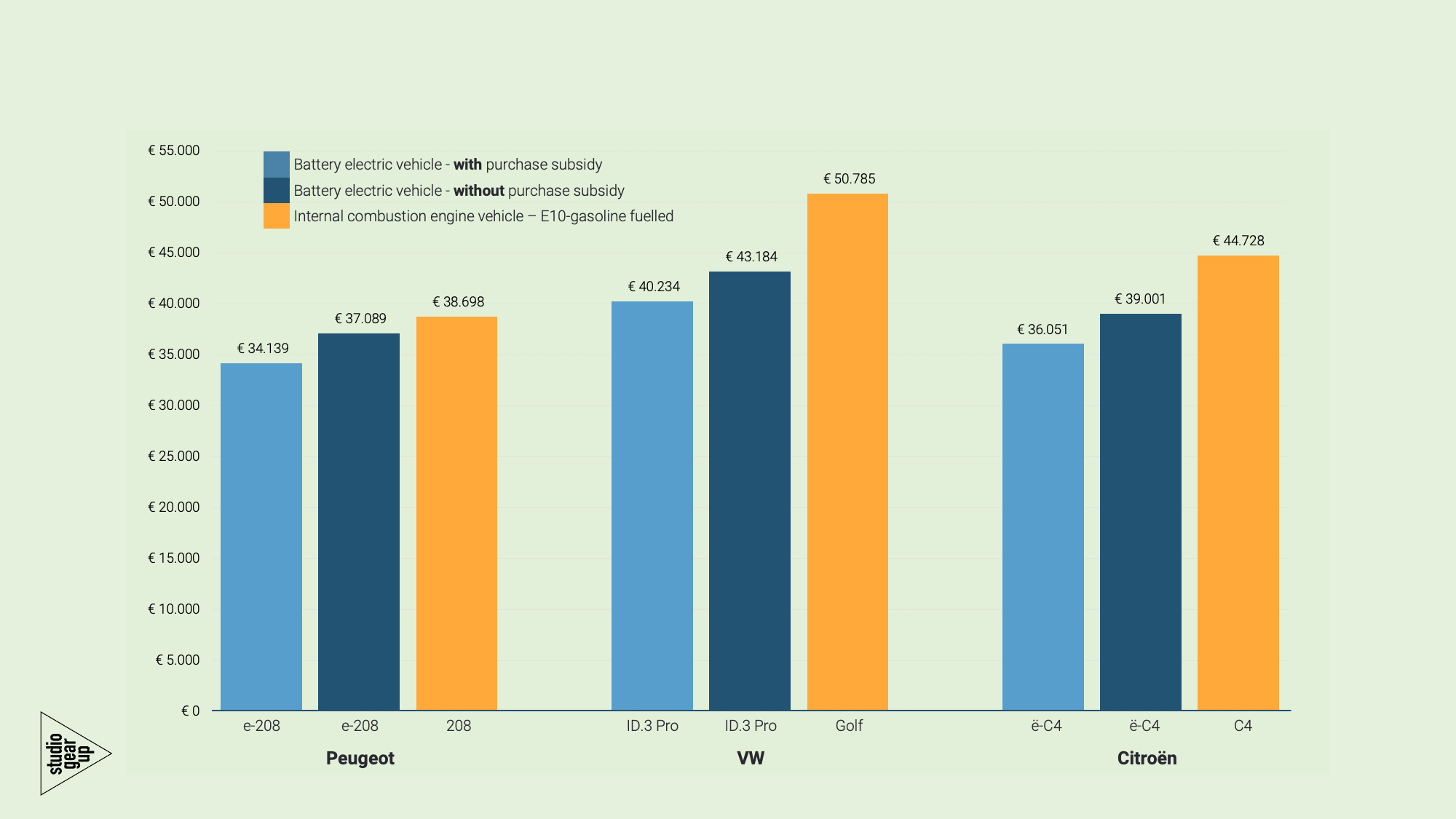

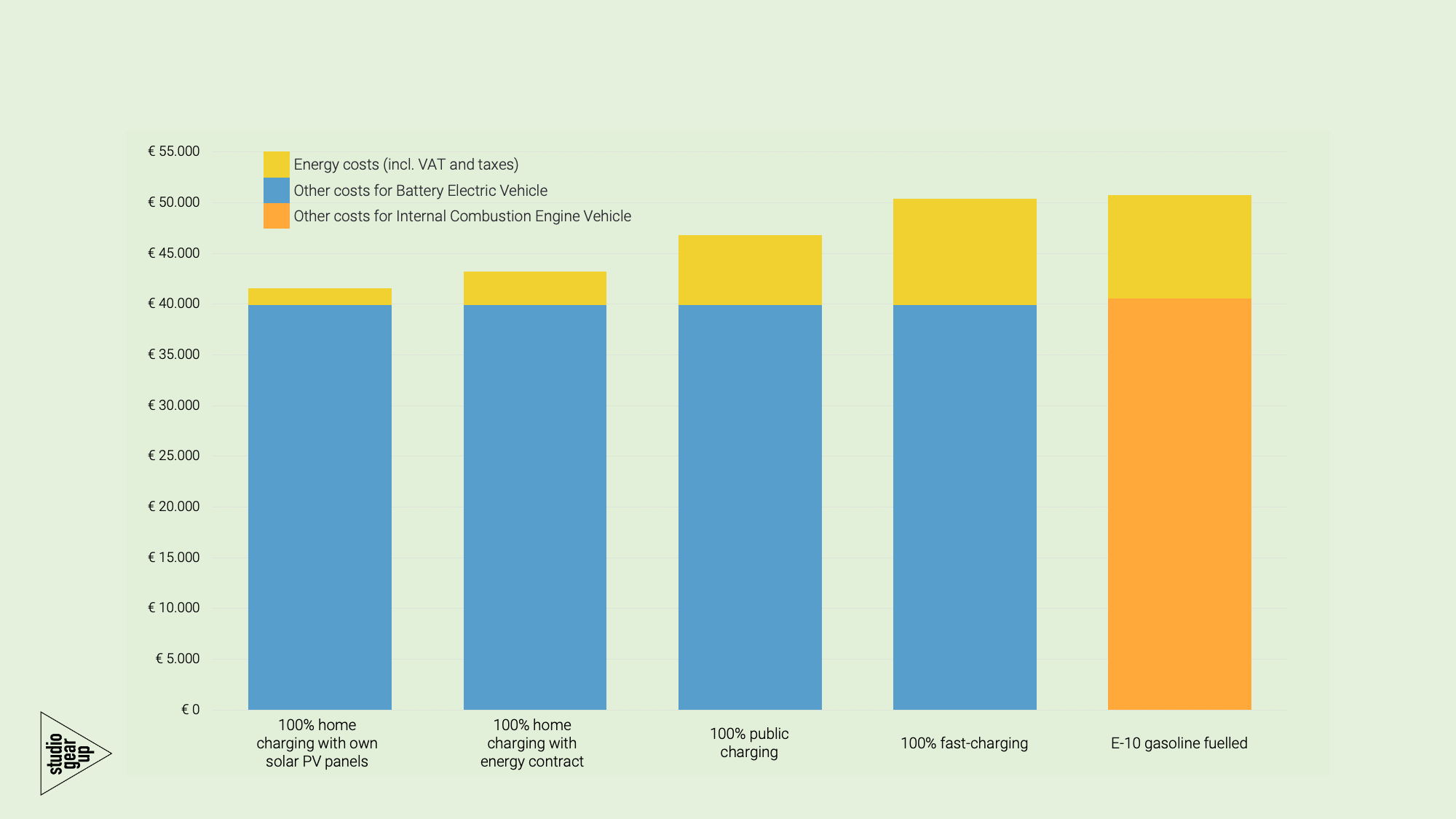

To illustrate the difference among the mode of BEV charging, Figure 2 shows that – when 100% public charging is assumed – the TCO of BEVs are increased due to the higher prices of electricity from public charging poles.

Noteworthy that only the TCO of Peugeot e-208 without purchase subsidy has turned over and rose over the TCO of Peugeot 208. In this case, the purchase subsidy could help to be on par with its ICEV counterpart.

Both the Volkswagen ID.3 and Citroen e-C4 stayed below the TCO of their ICEV counterpart even without the presence of governmental purchase subsidy, when 100% public charging is assumed. For a detailed cost breakdown of the TCO of BEVs with public charging and ICEVs, see Figure 10 and Figure 11 in the Annex part, at the end of this article.

Charging profiles per car model

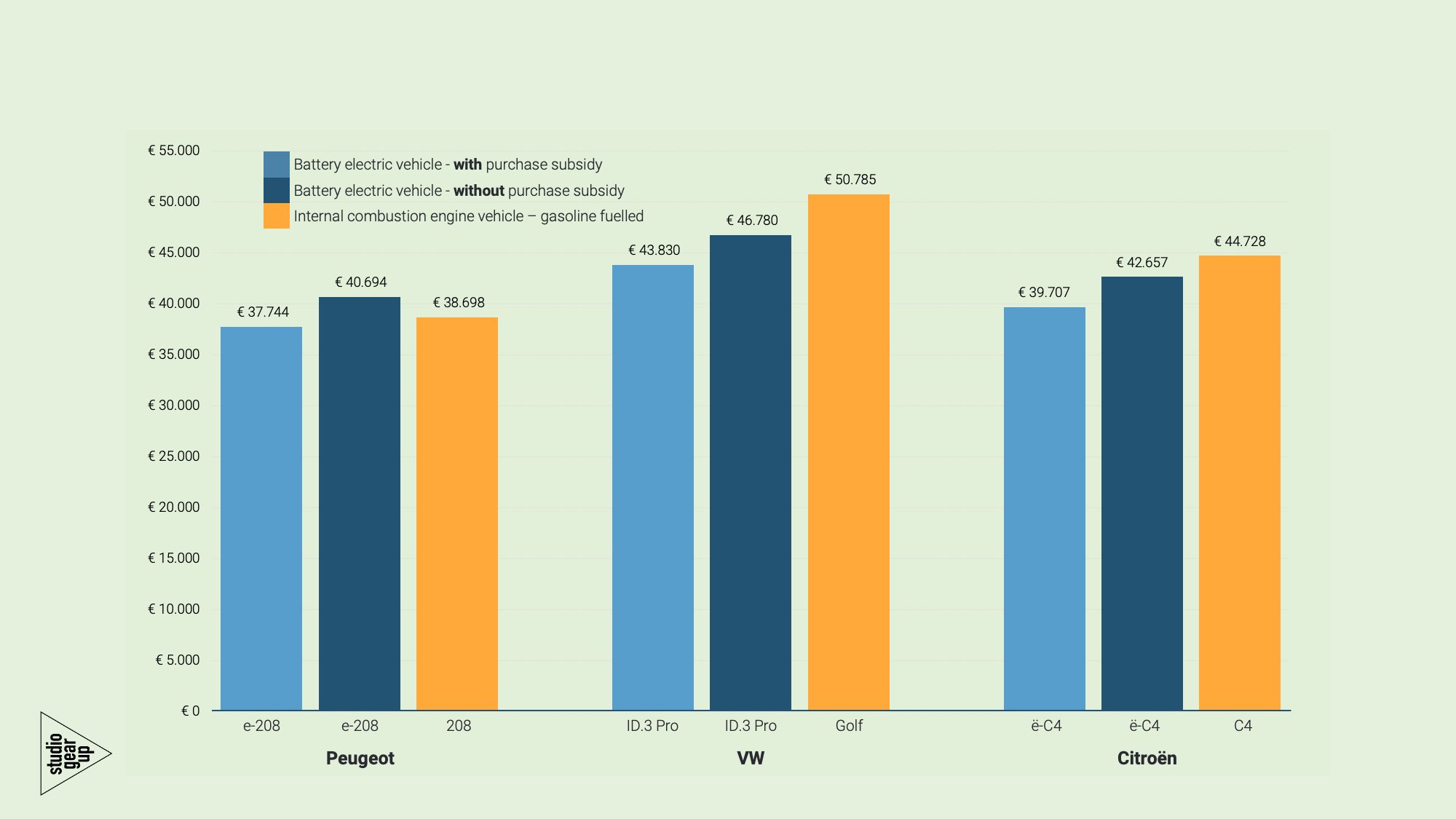

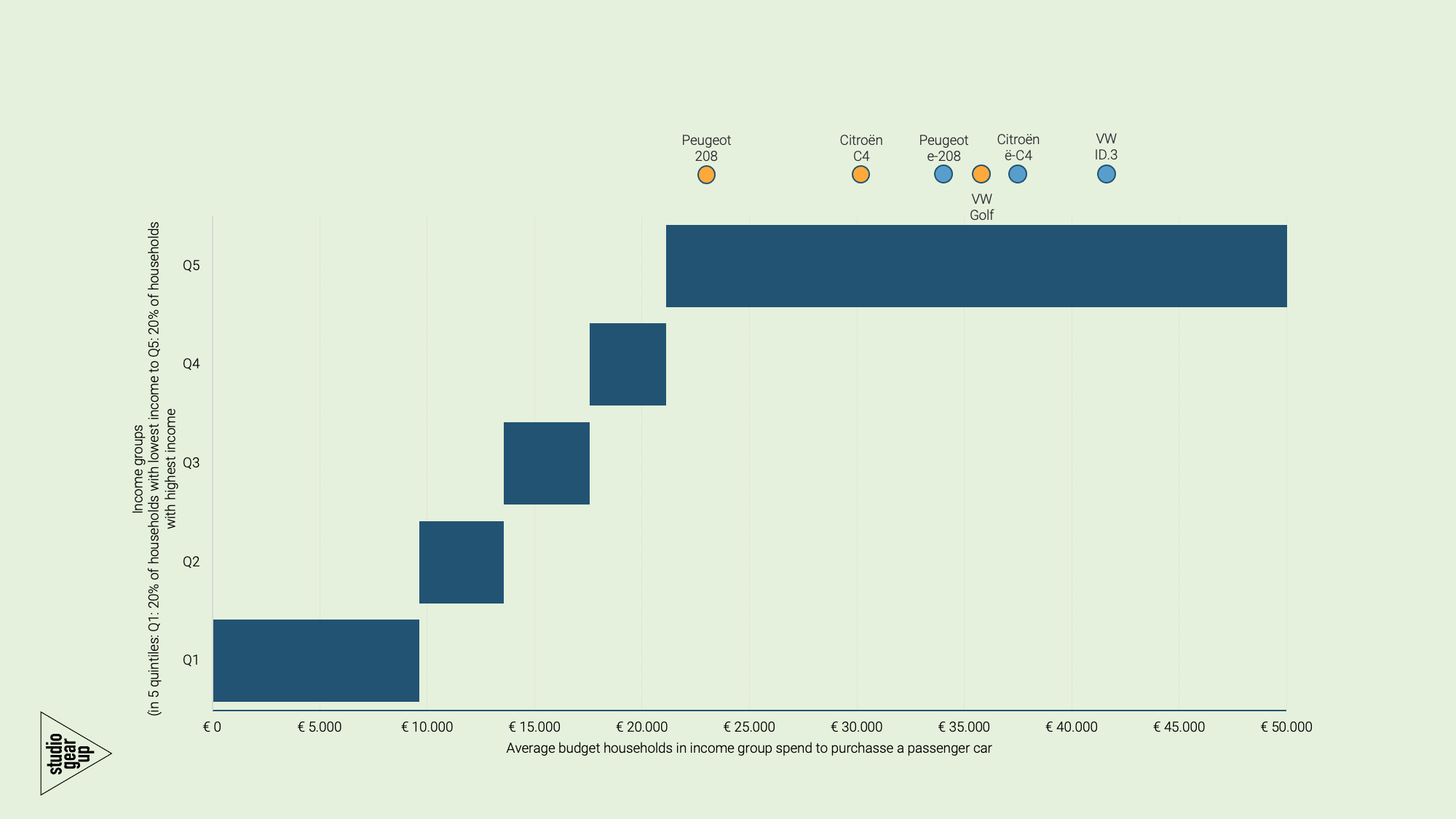

The affordability of BEVs is dependent of the mode of charging. Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the impact of the energy costs on the whole TCO of the different car models. While the blue and orange columns represent other cost categories within the TCO for the BEVs and ICEVs respectively, the yellow bars are purely the energy costs including all taxes.

The least costly mode of charging a battery electric vehicle is at home with the presence of solar panels, while fast charging proves to be as expensive as fuel for ICEVs. In case of fast charging, the share of the energy costs within the total cost of ownership is 25%, which is significantly higher than other modes of charging. The energy costs entail electricity cost including all taxes and levies for BEVs and fuel costs including all taxes and levies for ICEVs. Costs of home charging with solar panels is based on initial costs of solar panels divided by the lifetime of their operation, therefore the current balancing scheme (salderingsregeling) is not taken into account.

Even though it is unlikely that BEV owners would only charge their cars at fast charging poles, it is undeniable that current fast charging prices significantly increases the TCO of BEVs.

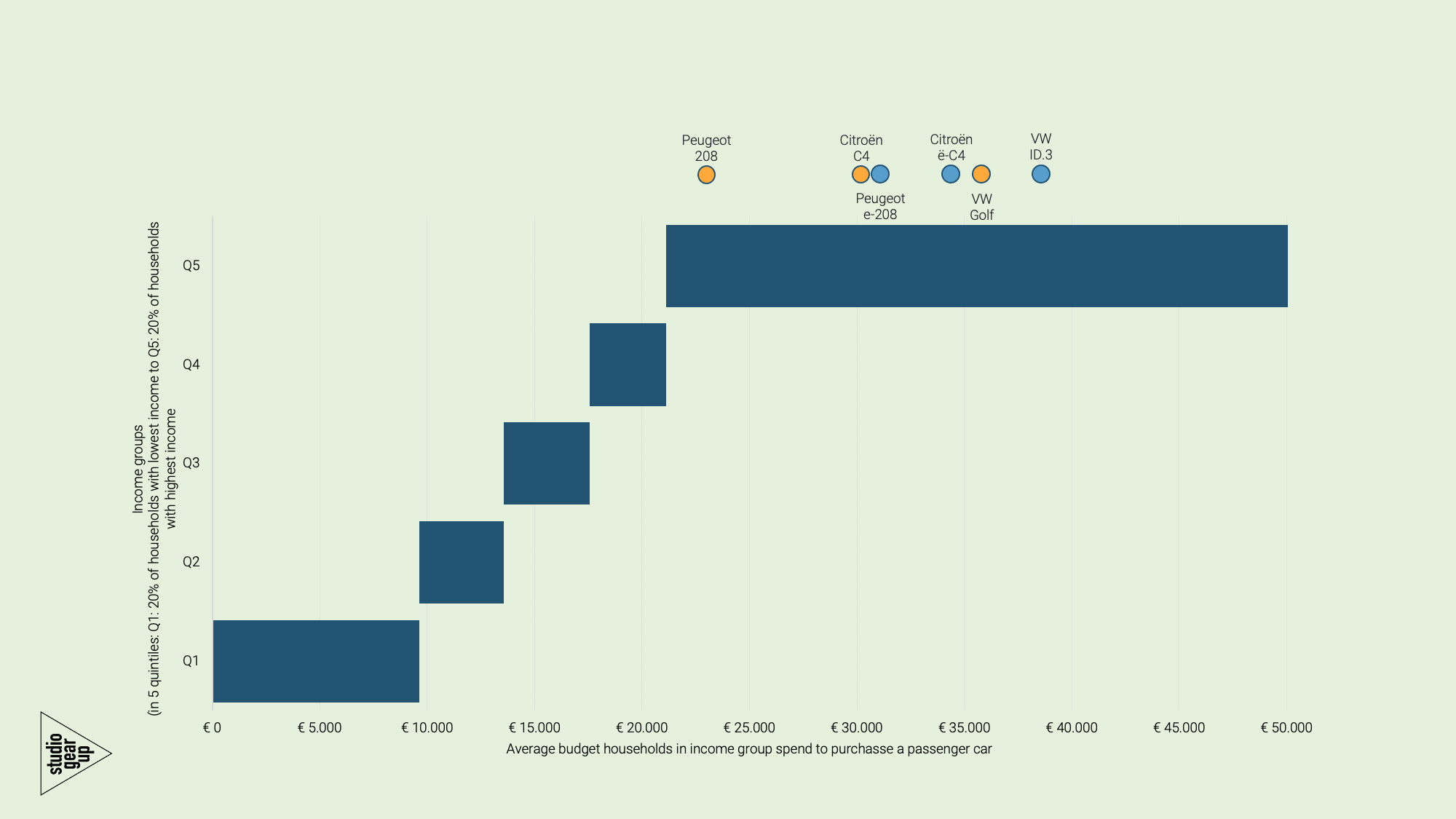

New passenger cars are only affordable to a minority of consumers

The purchase of new vehicles remains only affordable for the top income quantiles regardless of whether a subsidy is included or excluded. More specifically, all models within this analysis are for the top income quantile (Q5), with or without the purchase subsidy (€ 2 950) as shown on Figure 6 and Figure 7.

The implications of the constructed car purchase budget shows that the new car market is within reach only for the top 20% of the population. This further suggests that new cars – including BEVs – are still less accessible to the majority of the population. The current form of purchase subsidy does not serve the purpose of increasing the share of BEVs within the newly registered car fleet as only a minority of consumers could afford them. This is in line with the findings of Geerte et al. (2023)[4] uncovering barriers towards BEV uptake by private owners stating that new policy measures are needed to encourage the purchase of battery electric vehicles.

Key recommendations

Our recommendation, rooted in our analysis, of lowering the purchase price ceiling of the Private Electric Passenger Car Subsidy would convey the following indications:

- It would phase out unnecessary support for higher priced BEVs, as they are showing the most robust TCO advantage compared to ICEVs. They are already and will still be cheaper in the absence of the purchase subsidy.

- Redirecting the purchase subsidy towards lower-priced vehicles is also a shift towards income groups with lower subsidy support. They frequently rely on purchasing smaller cars and may lack the option to charge at home, depending on public charging which is potentially leading to a higher Total Cost of Ownership (TCO).

- It serves as a signal to car manufacturers that the Dutch government is inclined towards having smaller BEVs in its fleet. Therefore, the decision to subsidize only B-segment or smaller vehicles under € 35,000 reflects the government’s intention, recognizing the ultimate need for these cars in the used car market.

Download

The PDF of the full article (including annexes) can be downloaded here.

The report contains an annex with the breakdown of all costs in the total cost of ownership analysis.

In a second annex the methodology, assumptions and data sources for the total cost of ownership analysis built by studio Gear Up are described.

Footnotes

[1] https://www.autoweek.nl/autonieuws/artikel/er-zijn-in-2023-veel-meer-tweedehands-autos-verkocht/ and https://mijn.bovag.nl/actueel/nieuws/2024/januari/autoregistraties-2023-groei-door-inhaalslag-zet-do#:~:text=Volgens%20de%20officiële%20cijfers%20van,vergeleken%20met%20het%20voorgaande%20jaar.

[2] Transport & Environment, 2023, How leasing companies can become a key driver of affordable electric cars in the EU – Electrifying the used car market. https://www.transportenvironment.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/How-leasing-companies-can-become-a-key-driver-of-affordable-electric-cars-in-the-EU.pdf

[3] Subsidieregeling Elektrische Personenauto’s Particulieren (SEPP) https://www.rvo.nl/subsidies-financiering/sepp

[4] Geerte L. Paradies, Omar A. Usmani, Sam Lamboo, Ruud W. van den Brink (2023). Falling short in 2030: Simulating battery-electric vehicle adoption behaviour in the Netherlands. Energy Research & Social Science. Volume 97/102968. ISSN 2214-6296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.102968.

Read also:

Are we witnessing the end of the dominancy of ICEV vehicle registration in the Netherlands?

An analysis of the registration trends for passenger cars with combustion engines, electric engines and a combination of both

“Honey, I shrunk the car sales!”

An analysis of the 2022 registration of passenger cars in The Netherlands

Low carbon mobility with renewable fuels

A 2021 project for FuelsEurope on affordability and accessibility of passenger cars for EU consumers

Leave a Comment